“This will be a tap. The owl, with its wings outstretched, will be coming through the wall, and the branch it’s landing on will be the waterspout. We drew it first, then 3D printed it, and now it will be cast in brass as one piece, and hand chiselled to accentuate the feathers.”

I am standing in the former coach entrance to the oldest foundry in Ghent, Belgium, dating back to 1802, and the last working foundry within the city walls. Speaking, and handling the life size silicon model of an owl, is Peter van Cronenburg, the architectural hardware specialist and co-founder of van Cronenburg. The name is something of a closely guarded secret: a foundry patronised by those in the know for its finely crafted pieces, from the classic and simple to the eccentric and ornate. Their door knobs, bolts, handles and fasteners — finished in moody, patinated brass — are the discreet linchpins of interiors by Vincent Van Duysen, Ilse Crawford, Rose Uniacke, and Ken Fulk, to name a few. Under the co-direction of van Cronenburg and his wife, Régine Yvergneaux, around 20 craftspeople carry out the casting, forging, filing, chiselling, and polishing that goes into each piece of hardware, whether it’s a heritage door knob or a bespoke design. At any one time, the team can be working on over 100 projects occurring across the globe, ranging from small orders to full residential commissions, to the recasting of the entire facade of a 19th century building in NoHo, New York.

Back to overview

Back to overview

Architectural Hardware - The van Cronenburg Foundry

I must confess, I have only recently discovered the term architectural hardware and until now have not delved into the question of door knobs in any significant depth. In fact, I have lived for quite some time with one missing from my bedroom door, having sufficed with poking my finger through the hole in the wood whenever I have needed to open or close it; so it is with great pleasure and intrigue that I now correct my negligence on this subject.

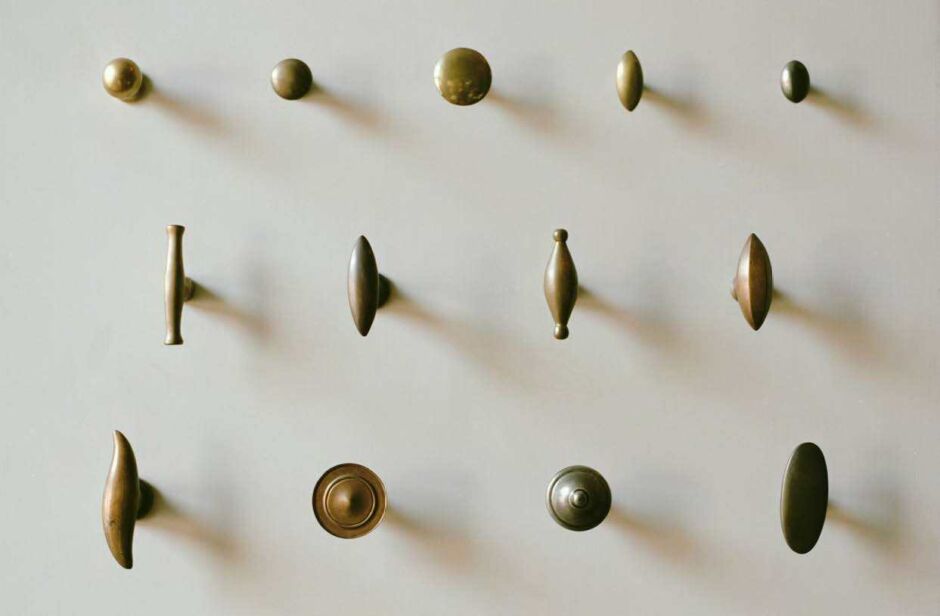

After putting the owl down, van Cronenburg draws my attention to the displays mounted in the shady entrance corridor, his eyes glinting behind round spectacles perched atop rosy, smiling cheeks. As I blink from the brightness of the street, I see brass keys styled in the clean lines of Art Deco and the florid forms of Art Nouveau. Crémones and espagnolettes, decorated in intricate acanthus leaves, are interspersed with rim locks concealing esoteric inner mechanisms. Elsewhere, a gently curving door handle flows into the form of a seated woman, her legs bent together, mermaid-like, beneath her torso. Another handle features the body of a snake wrapped about its length, each coil spaced perfectly to welcome my fingers in a natural grip.

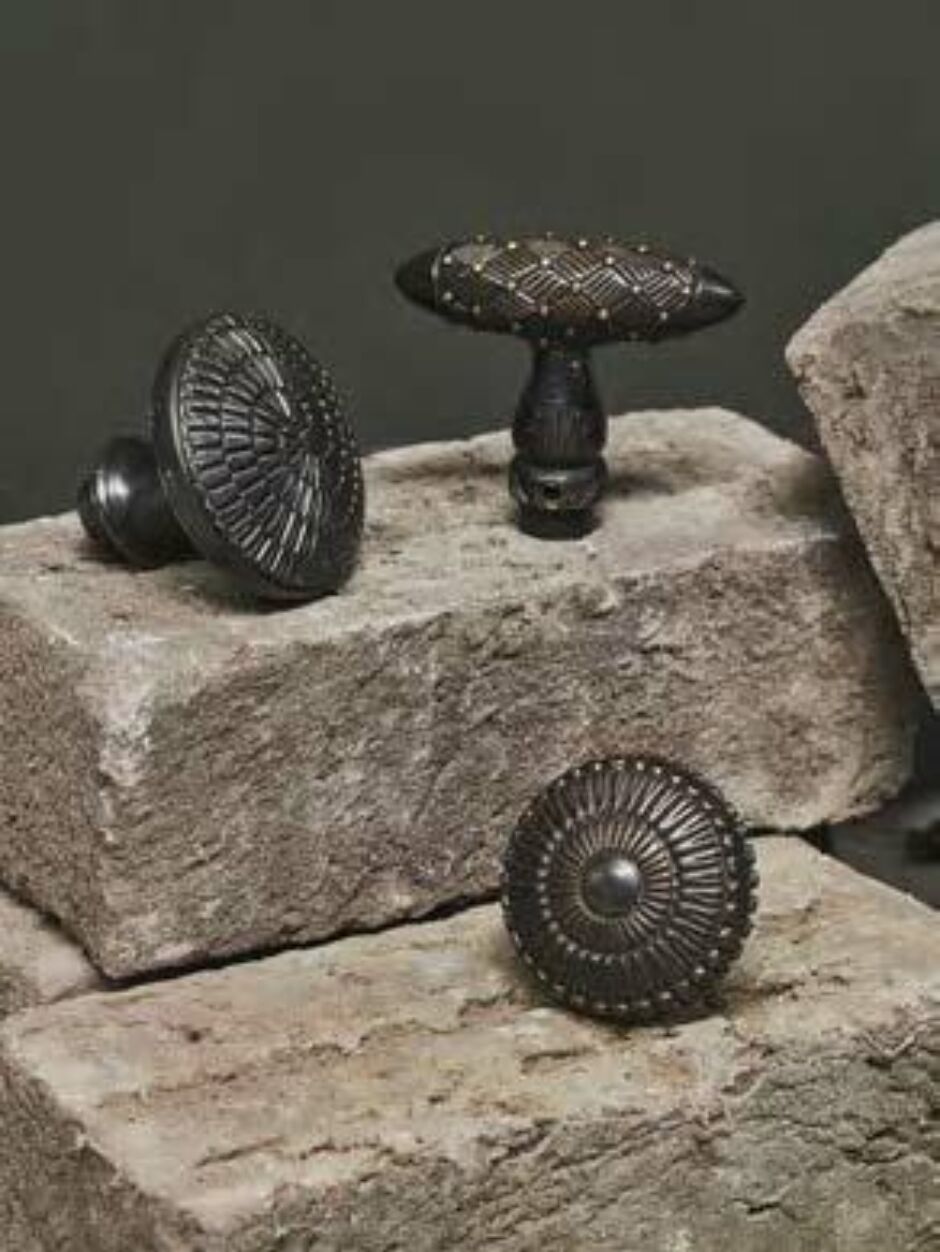

Perhaps the most appealing handles on display are the more understated forms. Ovals and teardrops, their smooth surfaces left unadorned, reveal the full depth of their dark, beguiling patina, which possesses an irresistible quality evocative of the sea at night. It is fixtures such as these that grace the doors and wardrobes of Hampshire’s Heckfield Place and Antwerp’s Graanmarkt 13.

My attention shifts to the whirs and rhythmic clunks rumbling from the end of the corridor. I follow van Cronenburg to the source of the noise. Craftspeople bend over roaring machinery, engaged in physical tasks of varying aggression: one craftsman grinds a piece of metal against a rotating cylinder, another buffets brass with a belt of whirling sandpaper, while another chisels precise details into a gleaming handle, fixed neatly in a vice. I strain to hear van Cronenburg’s cheerful lilt over the clamour around us. As I discover, his journey is an atypical one, although — as with all journeys — it possesses a natural logic that can only be gleaned retrospectively. Starting out as a cabinet maker in the 1980s, he became frustrated by the limited hardware available, and began producing his own, frequenting the foundry as a client from 1995. It wasn’t until 2008 when he discovered the owner was planning to sell that, overnight, he decided to buy it. “I never dreamt of taking this foundry over. I was a woodworker! But someone else was interested in the sale, and I realised all the models we had collected ourselves over the years, along with all the moulds the foundry had developed over its 200-year history, would have passed into their hands. I couldn’t let that happen.”

Van Cronenburg’s hardware collection now numbers in the thousands. It is unrivalled in Europe and is constantly growing as new designs are conceived, and antique pieces acquired. While most of the pieces derive from Europe, van Cronenburg and Yvergneaux collect from all conceivable periods of design, and no region of the globe is out of consideration. “If something is well made, I will buy it,” says van Cronenburg.

Two rooms to the rear of the workshop are dedicated to this immense archive. As I plunge after van Cronenburg through corridors of densely packed shelves, blanketed in alluring, uncountable brass, I recall exploring the many garden sheds (at last count, there were 11) belonging to my grandpa, who is something of a hoarder. Venturing further, I find myself enchanted by the marbled surface of a tiny, flat button of a door knob at one moment, and admiring an 18th century key with a deployable blade to fend off would-be burglars at the next. All this is soon to be moved, with each piece being transported to an expansive, purpose-built foundry and company headquarters on the outskirts of Ghent. Here, the team will be able to cast, forge and craft under one roof, as well as display the entire archive.

However, this archive is more than an enthusiast’s rarefied collection: it also serves a practical purpose. Unusual antique pieces can be recreated for clients by digitally scanning the object to make a 3D print, which is then used to create consecutive sand and lost wax casts. Once cast, the pieces are filed and polished to remove the casting seam. Finally, they are aged to darken the gleaming yellow of the fresh brass into the intriguing patina that is so crucial to the allure of all van Cronenburg hardware.

This final stage of the process, where the objects are rubbed and dipped in specific — and odorous — solutions, is perhaps the most transformative, and the most obscure. “The process is hundreds of years old,” says van Cronenburg. “When I first came to the foundry as a client, I knew which products to use, but I could never get the patina right. The pieces came out too dark or too dull. On the day I acquired the foundry from the previous owner, he finally revealed the secret.” Delightfully, van Cronenburg stops there, leaving this almost Masonic mystery as just that. “But the real finish comes later,” he continues. “As the handle is used over time, the patina rubs away to reveal a hint of the yellow beneath, but softer than before. All old homes appear this way"

"By inspecting the hardware, you can see how that person gripped the handles, which rooms they used most. You can see how they lived.”